“It’s About Your Rights and Freedom”

Millions of people around the world will celebrate Pride this month, marching in joyful parades and joining in a myriad of other festivities. But how many truly understand the origins of Pride and its significance for the movement for LGBTQ+ equality?

The Origins of Pride

The first Pride celebrations took place during the last week of June in 1970 as part of a one-year commemoration of the Stonewall Riots, an uprising of LGBTQ+ patrons and supporters at the Stonewall Inn. The Stonewall Inn was a club in the West Village of New York City that welcomed gay patrons at a time when the New York State Liquor Authority did not give licenses to establishments that served a gay clientele. To get around the law, the mafia-connected owners of the Stonewall Inn and other gay taverns paid off the police, essentially bribing them to look the other way.

In spite of these payoffs, the police conducted a raid at the Stonewall Inn, entering with a warrant in the early hours of June 28, 1969. As the police began arrests, a crowd formed outside the club and began throwing pennies and other objects. Within hours, a full-blown riot had erupted. Subsequent demonstrations continued for several days, with hundreds of New Yorkers coming out to express solidarity with the LGBTQ+ community.

Commemorating Stonewall

The Stonewall Riots might have fallen into obscurity, remembered only by participants. But they captured the attention of local media as well as national LGBTQ+ publications, and activists were determined to capitalize on the riots’ visibility. Brenda Howard, an openly bisexual woman who was active in the anti-war and feminist movements, took the lead in planning for a week-long celebration in New York City, to culminate in a 51-block march from Greenwich Village to Central Park. Activists in other cities, including Chicago and Los Angeles, also planned activities to coincide with the one-year anniversary. Organizers settled on creating a fun and joyful atmosphere at these events, thinking that it would be the best way to draw big crowds (Holland 2017).

An Antidote for Shame

It was L. Craig Schoonmaker, a longtime activist and member of the New York planning committee, who proposed “Pride” as a slogan that would embody the spirit of the commemoration and tie together various events. Years later, Schoonmaker summed up his reasoning—“The poison was shame, and the antidote [was] pride.” At the time, people were “very repressed, they were conflicted internally, and didn’t know how to come out and be proud. That’s how the movement was most useful, because they thought, ‘Maybe I should be proud’" (Zaltman 2015).

Schoonmaker could not have anticipated that Pride would one day be embraced by millions throughout the world. But it caught on quickly, with slogans like “Say it loud, gay is proud!” resounding in the streets of New York and other cities. As the crowds understood, this was a profound political statement. No longer willing to hide or feel shame in who they were, LGBTQ+ citizens were making themselves visible—out on the streets and public venues for all to see and hear.

The Start of a Movement?

In subsequent years, the Stonewall riots would increasingly be remembered as the catalyst for the modern gay rights movement. That is not entirely correct. Activists seized the opportunity to commemorate Stonewall at its one-year anniversary, and subsequent Pride celebrations perpetuated its memory. It was the commemoration of Stonewall--more than the riots themselves--that helped to propel the movement forward (Mattson 2019).

Without the efforts of activists around the country, the Stonewall Riots would likely have fallen into obscurity, recalled only by those who participated or witnessed the demonstrations. This had been the fate of earlier uprisings, which have only recently been rediscovered by historians studying the nearly century-long struggle for LGBTQ+ equality in the U.S. The first documented gay rights organization, the Society for Human Rights, was actually founded in Chicago back in 1924 ("Gay Rights" 2017).

The homophile movement, as it was then called, took a step forward in the 1950s, with the founding of two national organizations—the Mattachine Society for gay men and the lesbian organization known as Daughters of Bilitis. The movement gained even more steam the following decade, with formerly subdued events giving way to increasingly assertive actions and calls for “gay power” ("Gay Rights" 2017).

This heightened activism and organizational infrastructure made it possible for Pride celebrations to spread and keep the memory of Stonewall alive. Scholar Greggor Mattson explains, “Nationally coordinated activist commemorations were evidence of an LGBTQ movement that had rapidly grown in strength during the 1960s, not a movement sparked by a single riot.” He continues, “Stonewall was an achievement [of the gay rights movement,] and not its cause, and an achievement of collective memory and collective action . . . not the first LGBTQ riot or protest” (Mattson 2019).

Coming Out of the Shadows

After Stonewall, the gay rights movement moved increasingly out of the shadows, with new organizations, including the Gay Liberation Front and Transvestites Action Revolutionaries, embracing large public demonstrations and other forms of direct action in the 1970s. During the 1980s, ACT UP took on the mantle of increased militancy, forcing a reluctant U.S. government and health care industry to move more aggressively in the fight against AIDS. In subsequent decades, organizations kept up the fight against anti-LGBTQ+ bias in everything from housing and job discrimination to schoolyard bullying and hate crimes, achieving key victories along the way.

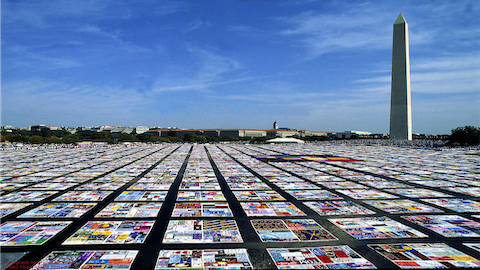

In the meantime, annual Pride celebrations continued to spread, becoming milestone events in the lives of LGBTQ+ individuals around the world, as well as opportunities for activists to raise awareness and press for equality. Presidents Bill Clinton and Barack Obama both issued executive orders declaring June to be Pride Month, and it’s now commonplace for organizations throughout the country, including corporations, to recognize and celebrate Pride.

“It’s Not About a Party”

Pride is clearly as relevant today as it was more than 50 years ago. L. Craig Schoonmaker explains why it continues to resonate so powerfully, “It works internally, and it makes people more self-assertive. It’s an understanding that people should be proud and not ashamed” (Zaltman 2015).

For Native New Yorker Anthony Zullo and others who recall Stonewall and the early Pride events, it’s thrilling to see millions of people turning out—proud and not ashamed--to marches across the country and around the world. But Zullo also has a cautionary reminder for his fellow revelers. The road for LGBTQ+ rights has been long and bumpy, with a great many twists, turns and outright setbacks along the way. With inequities persisting in employment, health care, housing and transgender rights, Zullo wants people to hold onto the essence of Pride. “It’s not about a party. It’s about your rights and freedom” (Gold 2019).

About the author--Kathleen Clark is Chief Learning Officer of Identiversity Inc. She lives with her family in Charlotte, NC and writes widely on topics relating to diversity, equity and inclusion.

References:

Editors, History.com. (2017, June 28). Gay Rights. History.com. https://www.history.com/topics/gay-rights/history-of-gay-rights

Gold, Michael. (2019, June 28). Stonewall Uprising: 50 Years Later, a Celebration Blends Pride and Resistance. New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/06/28/nyregion/stonewall-inn-50-anniversary.html

Holland, Brynn. (2017, June 9). How Activists Plotted the First Gay Pride Parade. History.com. https://www.history.com/news/how-activists-plotted-the-first-gay-pride-parades

Mattson, Grejor. (2019, June 12). The Stonewall Riots Didn't Start the Gay Rights Movement. JSTOR Daily. https://daily.jstor.org/the-stonewall-riots-didnt-start-the-gay-rights-movement/

Zaltman, Helen. (2015, June 3). Allusionist 12: Pride--Transcript. The Allusionist. https://www.theallusionist.org/transcripts/pride